Who Gets to Call Themselves Well-Read?

Some far-too-long thoughts on how arbitrary genre and taste can be, and how we evaluate the variety of what we read. (I'm so sorry for the length.)

Note: I created Succinctish for a quick weekly summary of what’s on my blog in a given week. This is not that—this is much more traditionally Substack (waxing poetic on the literary scene) and far too long. An outlier, promise.

For months now, I’ve been trying to put my thoughts on genre, age group, and snobbery into words. As a longtime book reviewer, I see a profound difference between criticism (good!) and blanket judgement (bad!)

I’m frustrated with those who argue we should review all books positively as well as those who are sweepingly derisive of whole genres. The need for escapism, rise of anti-intellectualism, dropping literacy rates (especially in children), etc. are all tangled together. Like all things: all of this is a more nuanced conversation that will not translate all that well to a polarized Internet. Criticism is not all-good or all-bad. Books are not all-good or all-bad by virtue of being books.

Still, I wanted to talk especially about the limitations I see people putting on their taste or what they consider a “good” book before knowing anything about its possible content. I’m going to try to resist the urge also to qualify myself a thousand times in anticipation of every possible “what about—” and just chat in good faith. This is not a particularly well-organized essay, and not at all up to my usual caliber. However, I wrote this five days deep into sinus infection antibiotics, ripping a redeye flight, and got myself all stirred up over the beginning of Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov in combination with Lyla Sage’s Swift and Saddled.

If you’re new here: I’ve been a book blogger for 14 years. I’ve been running my site, Words Like Silver, since the 7th grade. I’ve been a bookseller, literary agent intern, book club host, publishing intern, author, (brief) English major, blogger, and a journalist across major publications.

In essence, I try to read widely and often. Book publishing has many issues, and many modern takes on it re: quality boil down to either “publishing is practically fast fashion” versus “how dare you impose any editorial standards or critiques.” There are valid points on either side and, as always, I’m sure someone has already said exactly what I’m about to.

Later on, I’m going to use “BookTok” here as shorthand for the types of titles that your most arrogant, litfic, classic-loving friend would be derisive about, and “classics” for the shorthand of older, stuffier books grandfathered into the canon of so-called Great American writers and Brooklyn residents. The bookish Internet occasionally feels crowded by those bearing fluffy Kindles or moody loafer street fashions each assuming the other is tanking the literary scene (fully stereotyping here for brevity.)

Forgive me for flattening the labels for the purpose of this discussion (as they’re not mutually exclusive), but that underlines my whole point is that people aren’t specific enough when they’re judging whole genres. In my case, I think it’s fine for me to use shorthand to explain my genre annoyance because I’m not looking down on either extreme any more than the other. Everyone could benefit from a broader palate.

Why I’m Thinking About Genre & Taste & Why We Care So Much About It

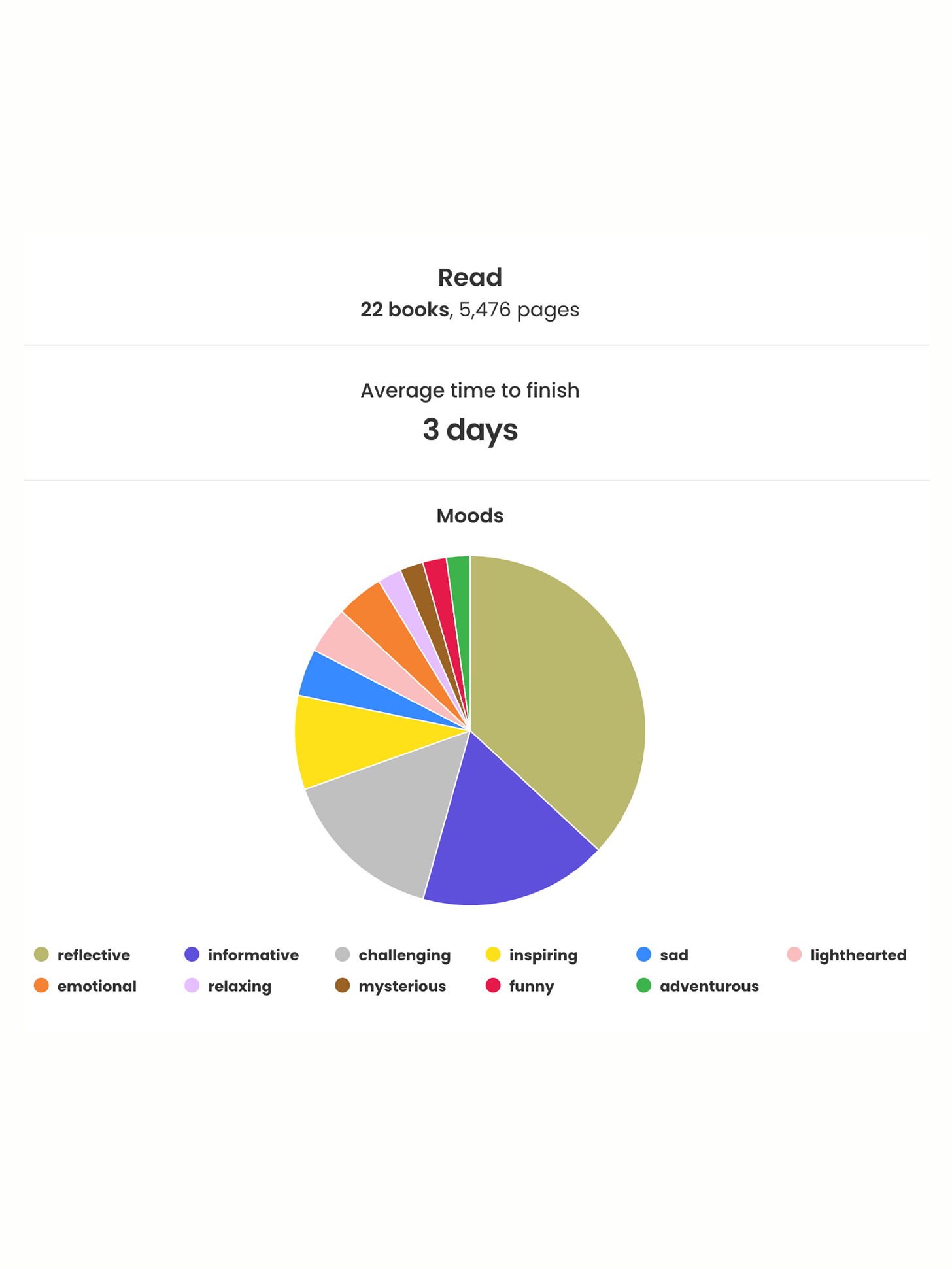

This year, I’ve read almost exclusively classics and philosophy. While undergoing various publishing processes for my own debut novel (after many, many manuscript revisions), I wanted to ignore the market for a beat. I avoided any and all possible comp titles that might me overthink what would sell; plus, I’d been on an existential kick. I’ve been bouncing between John Steinbeck and Plutarch and bell hooks and the Stoics.

Usually, I’m a “rabbit hole reader,” so this is just another one. I read children’s fiction and adult, speedy BookTok favorites and long-simmering ancient philosophy. I read authors I agree with and those I don’t, nonfiction and fiction, literary and commercial, modern and classic. When I find one book I love, I’ll branch out into ten other related reads in a sporadic combination of genres and styles, so the library of references I have within my brain is ridiculous (and—as others often say—”overwhelming.”) Associative and recursive to the max.

But for that exact reason, much of the posturing I see around whole literary genres and preferences—in such harsh, definitive lines—feels frankly ridiculous. So I wanted to hop on my soapbox and yell about it. As I put to another entertainment writer today, I’m passionately defensive against all the ways in which we dissuade people from discovering the love of reading.

Critique and judgement are different, and the latter seems antithetical to the fundamental openness and curiosity that defines reading as a pursuit whatsoever.

What Binaries Do We Use to Define Taste?

As an author steeped in publishing in various capacities, I often have querying writers ask me about genre, to which I say that I pitched my book differently depending on the agent and angle. In many cases, especially at the literary/commercial line, you can call the same book five different labels—and each will shift how it’s perceived. Since the neuroscience of reading hinges on how expectation and memory interact within your brain, that makes fundamental sense to me. But that’s also why I think people are far too judgmental about various genres too.

In the fall, I met a reader who pretty much exclusively read old books. I understood and agreed with plenty of his reasons (and personal preference doesn’t ruffle my feathers), but that catalyzed some of my questions about what “well-read” really means. What constituted a blind spot vs. a development of taste, for example. I often looked at his favorites list and thought of plenty of contemporary titles he’d love for the same themes, reasons, stylings, prose quality, and more. His binary: old vs. new.

Within contemporary book world, I’ve read plenty of litfic and have the lukewarm take that the literary designation has a whole lot more to do with social sphere and pedigree than people want to admit. Many seem to think that slapping “literary” onto the label makes the prose automatically exempt from the pedestrian elements of genre. My go-to litmus test is whether you would consider prose “spare” or “plain” without considering the source, because I think the tendency to reach for certain tone words while reviewing can point to the assumptions we carry into our experience of reading a book based on its positioning, author, how we label ourselves, etc.—myself included.

No book can exist in a vacuum, but that’s exactly why narrow genre judgements piss me off so much. To continue with the litfic example, literary work is the definition of “you get it or you don’t,” which is a sociological filtering experience. Sure, quality matters, but quality also matters in genre fiction and I’m not sure why some readers have such trouble admitting that. Their binary: litfic vs. genre. My reaction: same thing, different font.

I see it a lot in YA fiction, having grown up with it. Since I started reviewing books at age 13, I grew up immersed in that sphere. I’m fond of the genre, and I would also straightforwardly admit if my passionate defense of the work were based in nostalgia or an unwillingness to move on.1 When deciding how to categorize my own coming-of-age debut novel, I deeply considered how much it mattered to me that so many readers who pride themselves on being readers in persona sneer automatically at anything YA. Who, especially within journalism, would cheer for the book up until I decide its market positioning? Who might avoid it if classified as litfic because they assume it’s too serious or stuffy?

(Quick example of the YA bias: whenever there’s book industry drama circulating, and there is always book industry drama circulating, everyone will immediately go “it’s those YA authors again” even when the authors involved write something completely different. Another quick example: in all the takedowns of Ocean Vuong lately, I’ve seen various comments sections calling his work YA. Just because you dislike something does not shift its determined market classification.)

My personal offense is that I personally find a lot of anti-YA takes to be infantilizing, ignorant, and often cruel considering the evergreen popularity of coming-of-age narratives across genre, litfic, classics, etc.—but more on that later. In this example, the binary is: children’s fic vs. adult fiction. (There’s also a broader conversation about how that attitude reflects cultural condescension towards children as a whole, but I digress.)

There are expectations within every genre that determine reader satisfaction and don’t mean any book under that label is automatically shitty. My YA counterpoint, for example, is that pacing requirements are much stricter—for better and for worse. Opening chapters have to start off with a bang, and so you have way less room to screw around because of teenagers’ lower attention spans. We can talk about the degradation of focus in modernity and how that should alarm us, but many writers would also agree that pacing is the hardest 2So why is the assumption that adult fiction is automatically more intelligent?

What Your Reading Taste Says About You—or Doesn’t

It’s lovely to love what reaching for a certain writer says about your psychology. Books are signifiers, and we are constantly telling the world who we are based on the symbols with which we surround ourselves. (I’m a geek about the psychological role of aesthetics, so could chat about this for hours.) It’s natural to have preferences, to drift towards certain books, etc.

What I take issue with—on either end of the niche/classics/litfic vs. popular/modern/genre spectrum—is the assumption that preferring one book genre, style, or time period to another positions you morally or intellectually in a way that allows you to make sweeping blanket statement about shelves you don’t wander into and can’t bother to familiarize yourself with. If you’re going to critique whole sections of the bookstore, you have to read what you’re referencing or else I don’t care about your opinion.

Books, for the most part, don’t exist in a vacuum. They’re subjective experiences. As I wrote in a blog post on my (Lord) eight book rewrites, “a lot can affect the reading experience beyond objective plot, prose, etc,.: your expectation, newest unrelated interests, author context, current circumstances, and past and memories.”3

So: the Blind Test Matters

It’s nearly impossible to separate yourself out from the context of how you read or even select your books in the first place. But I do challenge you to read a book on two levels:

How you would read it naturally, based on how you’re wired and all its context, but also:

How would you feel about this book if it were blank, unformatted, author name stripped, off the street? In your hand, with no previous interaction with the material or its source.4

We automatically make exceptions for certain books all the time. For example: The language is stiff or it didn’t follow certain rules—but (unconsciously) “it’s a classic, so it was written in a different time and I’m going to try anyway.”

That’s an incredibly generous mode of reading you might be switching to on autopilot, one you’re not giving to the title published in 2023 simply because you know it was published in 2023—and it’s because you consider yourself a person who reads the classics or is “a good reader.”5

There are other problems baked into how we read and what we read, and who gets the book deals and who doesn’t. A quick, salient example: authors of color frequently encounter the criticism that white readers “don’t relate” to the character, a common counterpoint to this being “but you can relate to the princess or the billionaire no problem?” Hmm. 6

Basically, the lines at which we claim to be “rational” in our evaluation of which books are good are often bullshit, beyond certain basic thresholds. I’d argue those standards are much lower than readers might expect.

Probably a bell jar here, and it’s also why “buzz feeds buzz” and much of a book’s success has to do with self-fulfilling prophecy, publishers moving the needle, and word-of-mouth catching on.

While I won’t go into details (yet), my own debut novel is genre-blurring and cross-over, teetering right on the line of all of this. While pitching, it could go literary or commercial, YA or adult, cult-favorite award winner or BookTok sensation. And having been through years of querying, submission, conversation, edits—having worked with and chatted with and revised for multiple literary agencies at various points of the journey…

A book is a living document up until the point at which it is published. And even then, a book is a two-way experience and prism that has just as much to do with what you bring to it as what it objectively “is.”

Like, I called my own book Schrödinger’s Manuscript for years (and I’m still fond of the joke.)

And people at any given time are constantly sorting and shifting themselves based on the groups they classify themselves and the labels they’re giving themselves, and a book is no different. (As Fran Lebowitz has said, “The closest thing to a human being is a book.”)

Not to get too deep into the nitty-gritty science, but books are reflexive to our memories and associations, meaning that any of the (say) 70,000 words in a book can trigger a host of various combinations of emotions, reactions, and experiences within you. Reading is personalized.

And we narrow that down within publishing and every marketing decision we make that gets it to the right reader.7

And that’s still separate from my respect for the readers who engage in that type of lit—whatever it may be. I can rip on tech-bro nonfic or litfic or blurry-lined dark romance, but can also appreciate nuances within each genre. My critique should be based on individual titles—or I should at least be open to an experience with one changing my mind.

After going through so many gauntlets of traditional publishing, let me just say that you would be shocked by how many books you have a gut-reaction to based on how they’re labeled that could have gone a completely different direction based on what genre, age group, social circle it landed in. That’s the nature of marketing, baby.

You’ll edit and crystallize in one direction, sure (which is why I revised so much based on who I was with and what strategies we were gunning for), but because of that, I have little patience for the shorthand of sweeping genre quality judgments that have absolutely nothing to do with the words that make it onto the page and everything to do with the person sitting down to read them.

Similarly, many books that were released when I was a baby blogger didn’t boom until 10+ years later, so timing has everything to do with reception too—and reception can change.

My Favorite Example: Marcus Aurelius, Tumblr Poet Extraordinaire

My favorite example is that I read Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations last year (loved it) and my first thought was that the tone, cadence, insights, etc. felt so similar to Tumblr poetry á la Shinji Moon or Iain S. Thomas. But if I gave my local Ancient Roman reader a copy of I Wrote This for You, I know they would flinch and scoff and not read it in the same spirit.

Silly example, but feels relevant—

And similarly, you can argue that Meditations gets the Tumblr treatment because of modern translation and what we lose our gain in considering “accessibility” too (the satisfaction of stumbling through an obtuse passage vs. realizing that might be ego-padding more than necessary) but the ladies over at Lit Girl do a much finer job than I in their latest module discussing fanfiction, translation, and (for example) Emily Wilson’s interpretation of The Odyssey.

I think my personal answer to these genre questions of “being well-read” is to keep a healthy mix in your reading pipeline. I’d say “go high-low” but even the upmarket/downmarket correlation can unconsciously inject some perceived intellectual discernment into the picture. All in all, to pretend like a book’s label automatically determines whether or not a book is good just seems naive, at this point, so I’m continually surprised by how many people flat-out refuse to touch anything on specific shelves. It’s okay to have your preferences, but those are not universal descriptors of quality—and that goes for both sides of the “aisle,” so to speak.

If you called a book you hated something different, would you be more generous towards it? Yes? No? (We’ve also seen this objectively happen in various book launch case studies in which the marketing misrepresents the book and alienates whole populations of readers.) If you hesitated, you have your answer. Hard to do, but the payoff is worth it—I assure you.

Stay Curious—

There’s a lot more to unpack here, but I’d take pages and pages to discuss the modern publishing landscape and what’s seemingly rewarded vs. not in craft. There’s some we’ve lost by changing the rules of what’s an auto-reject for a literary agent evaluating thousands of pitch letters with 5-page attachments, and there’s some we’ve gained by holding manuscripts to a standard that doesn’t accept meta, meandering intros.

The answer to me is to put it all in Walt Whitman terms (via Ted Lasso) terms: be curious, not judgmental.

Literary taste can be a proxy for social positioning, sure, but are you actually exercising aesthetic judgment or have you tuned out entirely? Everyone can (and does) narrowly define “taste” in reductive ways that value context over literal content. Let’s just stay aware of it.

I've been using more highbrow fiction in a lot of my examples here because I've been loving on my classics lately, so those conversations are top of mind. But I'm just as critical of genre readers who refuse to look beyond the top twenty BookTok titles—or who beeline only to shelves decked out in that very distinctive color scheme, or dismiss anything written before 1980 as out of touch. As l've argued in recent blog posts, we're screwing ourselves over with recency bias, quick wins, and that sweet, sweet dopamine. Some of the misclassified dramas I've mentioned prove this too: readers who clamp down to one genre and refuse to explore outside it often need to go touch grass—in the gentlest way possible.

That's another conversation (All Hazelwood, Team Peeta, plagiarized bestsellers, etc.), but as I learned years ago as a teenager, disconnecting from Book Twitter drama—or its equivalent—is usually for the best. In fact, some readers of my favorite genres have proven themselves even less capable than solely-literary ones of handling critique. It’s made me veer towards reviewing popular titles less frequently, and I hate that I’ve started to worry about being shredded to pieces over a shallow, throwaway book opinion. I love y’all, but when I say I catch myself writing defensively in this take, it’s because of the culture built in that space. I think most of us can recognize the inflammation, addiction, and sameness that come from chasing escapism over friction. All things in balance.

Stereotypically literary readers, by contrast, may be more likely to imply you’re secretly an idiot than to publicly pile on. They probably won’t bully you off the Internet like a smut BookToker would (cue a thirst edit of Atticus Finch as ‘daddyyy’ and “Father Figure” getting stuck in my head for three hours), but they might have a holier-than-thou attitude that should have gotten rinsed out with a rewatch of Legally Blonde. “Don’t judge a book by its cover” in action. Both extremes suffer from “if you don’t share my exact opinion, you’re wrong.” BookTok just seems to veer more into you are a terrible person who deserves to get doxxed, while the literary snob equivalent seems to veer more into you are very stupid and inescapably shallow, so let the adults talk, sweetie.

There’s nuance and exception in all of this because I am using the extremes to talk about the average, which only underscores my point: you might be selling yourself short by refusing to recognize the same nuance within the collections of books themselves. Whole genres, age groups, time periods!

That book you either praise or condemn based on label was at auction with six publishers bidding each with vastly different angles and plans, so you saying “ugh, I never read [insert the genre it didn’t sell to] because it’s all [insert negative descriptor]” is ultimately empty. Even assuming the final, published product doesn’t shift at all during edits.

So: if you can’t make it through even a chapter of Melville without pivoting to a cotton-candy read that makes mind go numb, consider how you might have trained your brain to expect speed and convenience—and maybe check out The Molecule of More to understand the mechanisms you’re shortcutting in your pleasure system. If you find yourself getting riled up and viscerally upset (day ruined) over someone preferring a different brother in the bourbon-soaked vampire thriller unfolding on Bourbon Street, maybe add in some Walden (and feel free to point out that he aestheticized cottagecore while still enjoying material comforts!) There’s a conversational tie-in between a new and old book, a literary and a commercial book, a YA and an adult book—in every single title you encounter. When you add any book to your mental library, you’re constantly recalibrating its total.

In the opposite vein, if you flinch at a cartoonish college-set slow-burn romance that’s sold millions of copies and got a gaggle of twenty-somethings to start romanticizing Barnes & Noble, consider the it-factors you’re missing or the assumptions you’re making about anyone who enjoys what you find cringe-worthy. The difference between it landing in litfic, and getting an abstracted cover with a title like Margin, Exit, Telepathy that you praise for its “luminous, cerebral meditation on identity fragmentation within place”—smaller than you’d expect.

Even consider how some of your favorite books occasionally rebrand with new releases and different covers—to capture different segments of readers as they crop up. The same book can live a million lives.

And hey, even Ralph Waldo Emerson said that everyone should be reading the books of their time. Ray Bradbury recommended reading a poem and essay and short story before bed. Go head to head with me on literary references across the board. I dare you.

Regurgitating My List of Reading Takes

A book that is weird, old, or hard to read is not automatically better for you.

There are objective measures of quality, but I do think many of them have more to do with personal preference than we admit.

Those markers and rules change over time and are not set in stone. Some people are “allowed” to break creative expectations, and others aren’t. Consider why.

Some classics are classics for a reason.

Some classics are classics just because they’re classics.

We are trashing our attention spans, and should push through things that are boring.

But also, some things are just boring and that’s not an indictment.

Writers have always had varying levels of access, which also speaks to why some people are Great American Writers.

Some of what takes off or flops is sheer luck based on the right book at the right time.

Writers are unevenly rewarded. As Camus might say in The Plague, or Adam Alter would say in Anatomy of a Breakthrough, or as I said repeatedly during [redacted book process], luck stirs when provoked. You can work to give yourself the opportunities for luck. But some people just have more opportunity.

It’s probably good overall to see what’s evergreen vs. specific across time periods or genres. As F. Scott Fitzgerald Fitzgerald would say, you read to realize that your longings are universal longings and have endured too, and you’re less alone for that. Or James Baldwin: “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, or who have ever been alive.”

A lot of reading is self-fulfilling prophecy based in expectation, which is why mood reading exists!

You can’t really read a book in a vacuum.

Within a given book, everyone has something different they like or connect to. As my revision-induced existential crisis focused on, 70,000 words (or so) means at least 70,000 chances to win over or alienate a reader.

I don’t think you’re well-read if you don’t read across genres or types (or even ideologies.)

Having preferences is totally different from judging entire bookstore sections, even if you make shorthand jokes. (Ex: me joking that about professors cheating on their wives in litfic, or rolling my eyes at the “not like other girls” posturing of a fantasy heroine.)

Genre labeling is much more fluid than you think, especially within publishing.

It’s okay—and should be encouraged—to change and shift your taste at various times.

As a whole, I have a lot to say about how our modern culture (and our online presences) make it harder to change our minds and for others to allow us to.

Challenge yourself to also consider each book you read in a blind context thought experiment, if possible. I promise your world will feel a little bit bigger.

Market forces — no matter which “type of reader” you determine yourself to be — affect how we perceive quality.

There Are So Many Better Ways to Use Your Reader Ego!!

Not to get political, but reading is political! If you have a take on any of this, care about book bans. Care about social media platforms’ lobbying and how it’s all regulated, and what that does to classrooms and reading habits.

Culturally, care about how speeding up consumer expectations changes the broader cultural landscape and shifts “art” into “content” that’s become devalued. Care about how most authors can’t afford to become authors in the first place unless they have independent funding from partners, family wealth, etc. Care about who gets the opportunities for luck that allow their works to become classics in the first place. Care about the culture of pirating that directly steals from authors, or the LLM that will ensure that your favorite writer never sees their second deal.

Talk about the books you love. Critique the one you see circulating that you think deserves it without saying everyone who loves it must be either stupid or pretentious. Stop telling people not to review books honestly! Let people change their minds and get curious without waiting for the “gotcha.”

Maybe try a different kind of book every once in a while if you catch yourself defaulting. (I do.) If someone you love reads differently from you, try reading one of their favorites. It will make you feel closer to them, even if you never talk about it.

And then, to build for the next gen: bring a book out whenever you can. Read—out loud—to kids as early and often as is possible. Don’t take away their graphic novels or sci-fi in favor of pushing Anna Karenina on them because you think it will make them read the “right” books. Build the habit first, then their taste will naturally narrow, shift, change, adapt. Reading gets you curious about different things. It always gives me something new to love.

Overall, don’t waste your limited energy being dismissive towards what people choose to read if you can’t be bothered to pick up a book outside your blinders in the first place. (That is totally, totally different from justified—backed up—critique that just comes from you sitting down and reading that same book.)

Or, before I get this “what about” comment, you should absolutely feel fine calling out the girl posting Nazi propaganda in a cutesy book stack (a thing that happened this year), or refusing to platform material you hate or that is harmful. You can judge books from a distance, or think a genre’s not for you. But that’s different from positioning yourself as better or superior because of taste markers that can be startling arbitrary in the market.

I’m not sure why this term strikes me so much — maybe because I hesitated when buying a Book of the Month hat with the phrase. Or while self-consciously showing off my shelves to the classics reader in the fall and worrying that my October-favorite paranormal rereads might give them the “wrong idea” about my ability to intellectually spar. Everyone who reads is a reader, but everyone also has their blind spots. I just think we should be challenging them more consciously, especially those who build a career or following on discussing books and publishing.

I realize that even I am writing somewhat defensively right now in trying to address every possible element of the conversation, but alas: such is the price of broadcast publication versus genuine discussion. I’d love to chat about this, and I am open to you changing my mind. If you bring up a point I’ve considered, I’ll say so and that I forgot to include it. If you bring up a new one, I’ll concede or continue asking questions!

Of course, reading takes time which is limited so you can’t possibly get to be as open to other books or genres as would be ideal. Maybe just consider where you’re shortcutting yourself or could put in more effort towards well-roundedness. What is taste versus what is limitation? You can also be a genre diehard. I love that! I’m not speaking to you.

Knowing what you like isn’t a bad thing; my issue is with ego-related defensiveness masquerading as taste: “whataboutism” at its core, rampant online. We say books are subjective all the time but some of us aren’t practicing what we preach.

Everything’s more polarized nowadays (many, many books to cite on why that is), reader identity included. That’s changed, in my 14 years of book world. Cue a slew of essays I love about online belonging, the need for teams and cultural identifiers, stoking individualism, even my recent exhaustion with everyone needing to always have a take! etc,. If you’re a creative online, you’ve probably gotten the advice to niche down, because that’s what the platforms love. As book consumers, we internalize that too. Bouncing around different book types lately has illuminated for me how much that’s maybe shrunken us.

Reading as Listening?

Reading overall invokes a lot of the same science behind relationships, investment, and (as Simone Weil would say): a generosity of attention. I think about You’re Not Listening by Kate Murphy frequently, and have thought a lot lately about reading as a form of listening.

Books ask questions and are scientifically proven to be one of the few things that can actually change our minds without engaging our defenses in the way that conflict does in person. (I could geek out about indirect processing and why books are so good psychologically forever.)

I also care about the science of aesthetics, individual vs. collective identity, modern publishing, trying to be a better listener, the psychology of attention (digital minimalism being a resurgent kick of mine), performance vs. authenticity, literary gatekeeping, making people readers, art as political, the conscious devaluation of art, and everything that’s wrapped up in this.

Pick any topic, and I can probably give you the classic pick, literary pick, nonfiction (probably psych) pick, genre pick, craft or publishing pick, and the children’s pick to boot. Tell me I have bad taste. That’s fine. But name your preferred genre and I’ll make a connection between two books, classified entirely differently, that proves you might be coding the same content in opposite ways based on your own biases.

And if you’re going to be a snob about certain genres either way, at least get the damn label right. Don’t call romantasy YA when it’s not. Don’t call it romance when it’s written by a woman but serious literary fiction if the same exact book appeared written by a man. If you’re going to be judgmental, at least be accurate.

How well you read widely has everything to do with your openness and ability to listen. There’s a dose of elitism in some of this and a dose of sticking your head in the sand in some of the rest.

Even now, I have the sense all my thoughts on this aren’t coming across clearly enough, so definitely welcome any discussion especially if you disagree.

We could all benefit from not calling ourselves well-read until we really mean it. I still bought the hat though.

Do I agree that some people cling to visions of teenagers for too long? Absolutely—but then let’s also apply that logic to classic coming-of-age works or litfic dealing with young adults. If you’re going to hate on YA, be accurate, because you citing Fourth Wing-esque romantasy series as such undermines your entire point. Books are frequently mislabeled YA that are explicitly adult.

(Counterpoint: we’re losing our patience, hence the introduction of more burn-and-churn lit that rewards instant gratification, recycled stories and tropes, etc. etc.) We can introduce the whole “how many books can one person reasonably consume and understand in a year?” convo in which, again, the answer is: it depends. But hopping off my YA soapbox to get back to the point.

(For the record, that’s also why I love rereading, why I don’t do star ratings, and why I might pick up or put down a book and have a wildly different reaction to it. Right book, right time! And the layers build like a patina over time.)

Of course, we could dive into the unconscious influences/David Foster Wallace-style existential spiral of any language in the synopsis or description priming you to think about a book in a certain way, but—there would be aspects you love, and aspects you don’t love, but you’re probably applying them unevenly to the books you feel like most define you, or who you’d like to be, or who you’d like to be seen as.

There’s a broader conversation too here about publishing standards, knowing the rules so you can break them, who has permission to deviate, etc.

If you bristle at me “getting political” here, consider the factual evidence that publishing is over 90% white, and book bans primarily target marginalized authors.

As a quick aside, that’s what I find the role of the reviewer or the critic to be: not to unilaterally pan a book as unworthy of ever reaching any eyes, but to steer the material towards who it’s meant for. You can have your subjective opinions, taste, loves, standards, etc,. And we should champion certain levels of consideration and talent in plot, prose, messaging, etc,. But I love a negative review for the reason that books are two-way, relational, and partly about chemistry; we are matchmaking books to the right reader, not saying every book should be for every person. When I hate a book or think it’s “trash” or shouldn’t have gotten the deal or attention it did—sure, yeah, that’s my belief. But I don’t believe that my reaction automatically applies to every book classified in a similar way, and I’ll still try to suggest the type of reader I think it might be meant for, and that’s separate from my feelings about whether it deserved to be published in the first place. People have their own opinions on this, which is fine. Just my appeal to try to expand your comfort zone a little in terms of your gut instinct first impressions.